Self-Analysis Addict is an essay series examining the pop culture, books, and music that have shaped me as a person. It’s also a book of essays that you can purchase here.

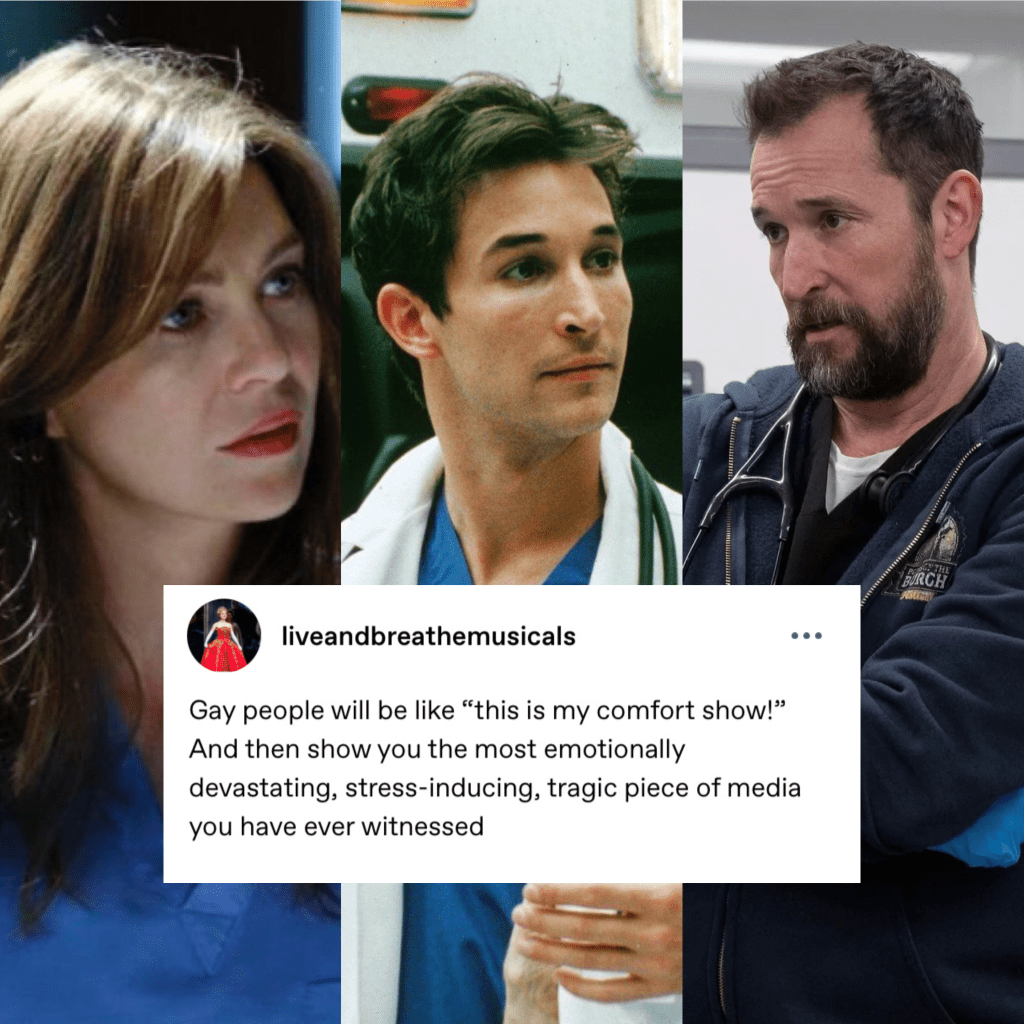

A few weeks ago, I finished watching the first season of The Pitt, the made-for-streaming medical drama whose style borrows heavily from the network-driven television dramas of yesteryear. The amount of buzz and worthy praise that the series has received is ironic, I find, given how many people across social media and beyond were chomping at the bit to find out what happens next. Not only does The Pitt borrow stylistically from any number of network procedural dramas of the last three decades — mainly ER, which is its own can of worms — but its distributor, HBO Max (or whatever they’re going by at the moment), chose to drop episodes on a weekly basis versus releasing an entire season at a time like a certain other streaming platform whose logo is a red N but who shall remain nameless.

The Pitt’s universal acclaim is more than justified, given its compelling portrayal not only of the daily, or rather hourly, challenges of being an emergency physician but also of what it’s like to exist in a field years after the grief and pandemonium of the COVID-19 pandemic still linger. As such, the first season of the series chronicles a single day shift in the emergency room of the Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center. The ringleader is Dr. Michael Rabinovitch (Noah Wyle), or Dr. Robby as he prefers to be called, on the day that happens to be the fourth anniversary of the passing of his esteemed colleague and mentor during the height of the pandemic.

What’s striking about The Pitt, and there are many things, is how it portrays not only how the medical fields at large are still grappling with the aftereffects of the pandemic four or five years in, but how Western culture is still collectively grieving the trauma. Lest we forget, we got our shots, wore our masks until they told us we didn’t have to anymore, and eventually got on with our lives — but very few of us properly grieved what we culturally experienced during the worst of those early years in the 2020s. There are reminders of this at every turn throughout the first season of The Pitt: from the drag of every cigarette charge nurse Dana Evans (Katherine LaNasa) lights, to the aggressivity in the trauma center’s waiting room, to the panic attack Dr. Robby finally succumbs to during the aftermath of a local shooting. We’re compelled because even though many of us might not work in medicine or emergency rooms, all of us remember what it was like living through the pandemic.

Interestingly enough, however, The Pitt is not a show about COVID. The worst we experience are Dr. Robby’s war flashbacks to the chaotic overwhelm that was his ER during what appears to be the first wave of the pandemic, and they aren’t too hard to stomach. Indeed, even if you aren’t someone generally entertained by medical dramas, The Pitt is a show about people — a sentiment that can also be applied to several other entries in the genre from years past. Roughly a year before The Pitt debuted, I had finished watching ER, the beloved long-running medical series that was once the highest-rated show on television during NBC’s “Must-See TV” era, from start to finish for the first time. It wasn’t a deliberate choice but rather something I put on to fill the void from Grey’s Anatomy, of which I watched (or rewatched) 18 seasons in under a year.

My introduction to Grey’s Anatomy was not in the 2020s, of course. I was around for its reign as the most-talked about network show in the mid to late 2000s, when girls at the sixth grade lunch table gushed about the graphic surgical procedure their parents let them stay up late on Thursday night to watch. My mom was an avid fan, so I saw bits and pieces, waiting for the moment when I was finally “old enough” to watch it for myself on DVDs borrowed from the library. I lost track somewhere around season six, eventually waiting until 2021 to start over from the beginning on Netflix — otherwise known as the year we were expected to return to some kind of “hybrid” version of our old lives while an uncontrollable virus still ravaged our world. This also happened to be when I went on antidepressants for the first time, a decision that changed my life forever. I don’t remember feeling better so much as I remember watching Grey’s Anatomy to nurse me back to health.

Throughout that first tumultuous year of mental health medication, of all the work just getting started and little victories no one would see, Grey’s Anatomy never failed to be there for me. Usually I’m a very mood-specific consumer, whether it be books, movies, or TV. But that year, it didn’t matter what my mood was — Grey’s satisfied the craving. It bandaged the wound after explaining it to me in terms I never would have put it. I often recall back to Meredith’s (Ellen Pompeo) fall into the frigid water during the ferry crash in season three, the moment in which she didn’t swim and stopped fighting for herself, as the moment where I realized I needed to keep fighting for myself. It didn’t solve all my problems, but Grey’s Anatomy was there while I was figuring them out — because it’s not just a show about surgeons. Grey’s Anatomy is a show about trauma, something we can all relate to at one time or another. That is, until I ran out of episodes, at least at the time. So I took a trip over to Cook County General.

I’ve often wondered if my fascination with television medical dramas stems from my mother being a nurse, of always having someone close by with medical knowledge, advice, and split-second thinking. Her profession is certainly what drives her own interest in medical television shows, given that my mom never missed an episode of ER during its first several seasons. I wasn’t old enough to ever watch even a bit of it with her — it came on at 10 p.m. — but watching it for the first time myself as an adult felt like sharing something in common with her, now that I was old enough. My impulse buy of the complete series set, all 15 seasons, on DVD during a Black Friday sale did not go to waste. Rather than have it be my constant companion as I did with Grey’s, my initial journey with ER was something like the television equivalent of a nightly glass of wine: watching the show during the day just didn’t hit the same as turning everything off and watching it late at night. It took me well over a year to get through the entirety of ER, and I missed it so much when I was done that I might’ve just started right back over from the beginning.

Medical dramas are far from the only kind of television program that compel me, but as I’ve grown older I’ve wondered what it is about them — their chaos, their severity, their deeply felt, real-world problems — that makes me feel comforted. In the introduction to her essay collection The 2000s Made Me Gay, author Grace Perry recalls happening to have niche medical knowledge that she learned from Grey’s Anatomy during her own brother’s cancer treatment, and how she really just wished in that moment that her friends from Grey Sloan Memorial Hospital were real and could help her. There’s something about that sentiment that has always resonated with me on a pop cultural level, since despite the unfortunate fact that these doctors aren’t real, I immediately feel safe when Dr. Greene (Anthony Edwards) or Dr. Carter (also Noah Wyle) greet their next patient on the gurney in the ambulance bay.

In spite of their hectic, uncertain nature, watching high-stakes medical dramas like Grey’s Anatomy, ER, or The Pitt feels like making my outsides match my insides: as my antidepressant journey led me to a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, watching television series like these sometimes matches the level of chaos happening inside my head on any given day. Watching these shows isn’t so much stressful as it is a release, a way of visualizing my anxiety and sometimes contextualizing my own angst with the (fictional) struggles of others. Which is not to say that they make me apply an “others surely have it worst” mentality, but rather that they remind me of my humanity: that even in spite of so much tragedy and death, miracles happen, solutions are found, new approaches are developed. It’s far from an answer, but in the fictional Seattle, Chicago, or Pittsburgh, sometimes it’s enough to get by.